Art Representing Taking Everything for the Family So They Could Kive Their Dreams

Edvard Munch, who never married, called his paintings his children and hated to be separated from them. Living alone on his estate outside Oslo for the last 27 years of his life, increasingly revered and increasingly isolated, he surrounded himself with work that dated to the start of his long career. Upon his death in 1944, at the age of 80, the authorities discovered—backside locked doors on the second floor of his house—a collection of 1,008 paintings, 4,443 drawings and 15,391 prints, also equally woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, lithographic stones, woodcut blocks, copperplates and photographs. Yet in a final irony of his difficult life, Munch is famous today equally the creator of a single image, which has obscured his overall achievement as a pioneering and influential painter and printmaker.

Munch's The Scream is an icon of modern art, a Mona Lisa for our time. Equally Leonardo da Vinci evoked a Renaissance ideal of serenity and self-control, Munch defined how we see our ain historic period—wracked with anxiety and uncertainty. His painting of a sexless, twisted, fetal-faced creature, with oral cavity and eyes open up broad in a shriek of horror, re-created a vision that had seized him every bit he walked ane evening in his youth with two friends at sunset. As he later described it, the "air turned to claret" and the "faces of my comrades became a garish xanthous-white." Vibrating in his ears he heard "a huge endless scream course through nature." He made 2 oil paintings, two pastels and numerous prints of the image; the two paintings belong to Oslo'due south National Gallery and to the Munch Museum, as well in Oslo. Both take been stolen in recent years, and the Munch Museum'due south is nonetheless missing. The thefts have only added posthumous misfortune and notoriety to a life filled with both, and the added attention to the purloined paradigm has further distorted the artist's reputation.

With the aim of correcting the balance, a major retrospective of Munch'southward work, the starting time to exist held in an American museum in almost 30 years, opened last month at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. "Everybody knows, but everybody doesn't know Munch," says Kynaston McShine, the MoMA curator-at-big who organized the exhibition. "They all have the idea that they know Munch, just they really don't."

The Munch who materializes in this bear witness is a restless innovator whose personal tragedies, sicknesses and failures fed his creative work. "My fright of life is necessary to me, every bit is my disease," he once wrote. "Without feet and disease, I am a ship without a rudder....My sufferings are role of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art." Munch believed that a painter mustn't simply transcribe external reality simply should record the affect a remembered scene had on his own sensibility. Equally demonstrated in a recent exhibition of cocky-portraits at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, much of Munch'due south work tin can be seen as self-portraiture. Even for an artist, he was uncommonly narcissistic. "Munch's work is like a visual autobiography," McShine observes.

Although he began his artistic career as a pupil of Norwegian painter Christian Krohg, who advocated the realistic delineation of contemporary life known as Naturalism, Munch developed a psychologically charged and expressive style to transmit emotional awareness. Indeed, past the time he raised his brush to the easel, he typically no longer paid attending to his model. "I do not pigment what I see, simply what I saw," he once explained. Influenced as a young man by his exposure in Paris to the work of Gauguin and van Gogh, who both rejected the academic conventions of the official Salon, he progressed toward simplified forms and blocks of intense color with the avowed purpose of conveying potent feelings. In early 1890, in a huff, Munch quit the class of an esteemed Parisian painting teacher who had criticized him for portraying a rosy brick wall in the light-green shades that appeared to him in a retinal afterimage. In means that antagonized the contemporary fine art critics, who defendant him of exhibiting "a discarded half-rubbed-out sketch" and mocked his "random blobs of colour," he would incorporate into his paintings graffiti-similar scrawls, or thin his pigment and let it baste freely.

The radical simplicity of his woodcut technique, in which he often used just 1 brilliant color and exposed the grain of the wood on the print, can still seem startlingly new. For the woodcuts, he adult his own method, incising the prototype with rough broad strokes and cut the finished woodblocks into sections that he inked separately. His printmaking style, equally well as the bold composition and color palette of his paintings, would securely influence the German language Expressionists of the early 20th century, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Baronial Macke. Characteristically, though, Munch shunned the role of mentor. He preferred to stand apart.

"He wanted to exist regarded equally a contemporary artist, not an old master," says Gerd Woll, senior curator at the Munch Museum. He embraced chance fearlessly. Visitors to his studio were shocked when they saw that he had left his paintings out of doors in all kinds of weather. "From the beginning years, the criticism of Munch was that he didn't finish his paintings, they were sketches and starts," Woll says. "This was true, if you compare them to paintings in the Salon. Simply he wanted them to wait unfinished. He wanted them to be raw and crude, and not smooth and shiny." It was emotion he wanted to depict. "It's not the chair that should be painted," he once wrote, "but what a person has felt at the sight of it."

I of Munch'southward earliest memories was of his mother, confined with tuberculosis, gazing wistfully from her chair at the fields that stretched exterior the window of their firm in Kristiania (now Oslo). She died in 1868, leaving Edvard, who was 5, his three sisters and younger brother in the care of her much older husband, Christian, a doctor imbued with a religiosity that oftentimes darkened into gloomy fanaticism. Edvard'southward aunt Karen came to live with the family unit, but the male child's deepest affection resided with Sophie, his older sister. Her death nine years later on at historic period 15, also of tuberculosis, lacerated him for life. Dying, she asked to be lifted out of bed and placed in a chair; Munch, who painted many compositions of her affliction and concluding days, kept that chair until his decease. (Today information technology is owned by the Munch Museum.)

Compounding Edvard'south misery was his own fragile health. As Sue Prideaux recounts in her new biography, Edvard Munch: Backside The Scream, he had tuberculosis and spit claret as a male child. His father's expressed preference for the next globe (an alarming trait in a physician) simply amplified the son's sense of death's imminence. One of Munch'due south finest self-portraits, a lithograph of 1895, depicts his head and clerical-looking collar materializing out of a black background; a thin white band at the elevation of the work contains his name and the twelvemonth, and a corresponding strip beneath features a skeletal arm. "I inherited two of mankind's about frightful enemies—the heritage of consumption and insanity—illness and madness and expiry were the black angels that stood at my cradle," he wrote in an undated individual journal. In a never-ending saga of woe, i of Edvard's sisters spent most of her life institutionalized for mental illness, and his one blood brother, who had seemed atypically robust for a Munch, died suddenly of pneumonia at 30. But his youngest sister, Inger, who like him never married, survived into old age.

Edvard's precocious talent was recognized early on. How apace his fine art (and his personality) evolved can be seen from two self-portraits. A small, three-quarters profile on cardboard, painted in 1881-82 when he was but eighteen, depicts the creative person'due south classic expert looks—straight nose, cupid'south-bow oral fissure, strong chin—with a fine castor and academic definiteness. 5 years later, Munch'southward palette-knife work in a larger self-portrait is impressionistic and splotchy. His hair and throat blur into the background; his lowered gaze and outthrust chin lend him an insolent air; and the cherry-red rims of his eyes suggest boozy, sleepless nights, the start of a long descent into alcoholism.

For a full-length portrait in 1889 of Hans Jaeger, the nihilist at the center of the maverick crowd in Kristiania with whom Munch increasingly fraternized, the artist posed the notorious author in a slouch on a sofa with a glass tumbler on the tabular array in front of him and a hat depression on his brow. Jaeger's head is cater-corner and his eyes jut frontward in a pose both arrogant and dissolute. Along with psychological astuteness, the compelling portrait demonstrates Munch's awareness of recent developments in painting. The dappled blue-and-greyness brushwork of Jaeger's coat suggests Impressionism, especially the work of Cézanne, which the Norwegian may accept seen on trips to Paris in 1885 and 1889.

For Christian Munch, who was struggling to pay the expenses of his son's teaching, Edvard's clan with dubious companions was a source of anguish. Edvard, as well, was torn. Though he lacked his father's faith in God, he had notwithstanding inherited his sense of guilt. Reflecting later on his bohemian friends and their encompass of costless beloved, he wrote: "God—and everything was overthrown—everyone raging in a wild, deranged dance of life....But I could not set up myself free from my fearfulness of life and thoughts of eternal life."

His first sexual experience apparently took identify in the summertime of 1885, when he was 21, with Millie Thaulow, the wife of a distant cousin. They would run into in the forest near the mannerly fishing hamlet of Aasgaardstrand. He was maddened and thrilled while the relationship lasted and tormented and desolate when Millie ended it afterwards 2 years. The theme of a forlorn man and a dominating adult female fascinated Munch. In ane of his most historic images, Vampire (1893-94), a red-haired woman can be seen sinking her mouth into the neck of a disconsolate-looking lover, her tresses streaming over him like poisonous tendrils. In some other major painting, his 1894 Ashes, a woman reminiscent of Millie confronts the viewer, her white dress unbuttoned to reveal a ruby slip, her hands raised to the sides of her head while a distraught lover holds his head in despair.

Munch was in Paris in Nov 1889 when a friend delivered a letter to him. Verifying that information technology contained bad news, he bid the friend cheerio and went lonely to a nearby eatery, deserted except for a couple of waiters, where he read that his father had died of a stroke. Although their relationship had been fraught—"He didn't understand my needs; I didn't understand the things he prized almost highly," Munch one time observed—the death unhinged him. Now head of a financially pressed family, he was sobered past the responsibleness and gripped by remorse that he had not been with his father when he died. Considering of this absence, he could not release his feelings of grief into a painting of the death scene, as he had done when his mother and his sister Sophie died. Night in Saint Cloud (painted in 1890), a moody, blue interior of his suburban Paris apartment, captures his state of mind. In it, a shadowy figure in a summit hat—his roommate, Danish poet Emanuel Goldstein—stares out a window at the brilliant lights on the Seine River. Evening lite, streaming through a mullioned window, casts a symbolic pattern of a cross onto the floor, evoking the spirit of his devout father.

Following his father's death, Munch embarked on the well-nigh productive—if about troubled—stage of his life. Dividing his time betwixt Paris and Berlin, he undertook a serial of paintings that he called The Frieze of Life. He produced 22 works as part of the series for a 1902 exhibition of the frieze in Berlin. Suggestive of his state of listen, the paintings bore such titles as Melancholy, Jealousy, Despair, Anxiety, Expiry in the Sickroom and The Scream, which he painted in 1893. His style varies dramatically during this catamenia, depending on the emotion he was trying to communicate in a detail painting. He turned to an Art Nouveau sultriness for Madonna (1894-95) and a stylized, psychologically laden Symbolism for Summer Night'southward Dream (1893). In his superb Cocky-portrait with Cigarette of 1895, painted while he was feverishly engaged with The Frieze of Life, he employed the flickering brushwork of Whistler, scraping and rubbing at the suit jacket so that his body appears as evanescent equally the fume that trails from the cigarette he holds smoldering near his center. In Decease in the Sickroom, a moving evocation of Sophie's death painted in 1893, he adopted the assuming graphic outlines of van Gogh, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec. In it, he and his sisters loom in the foreground, while his aunt and praying begetter attend to the dying girl, who is obscured by her chair. Across the vast space that divides the living siblings (portrayed every bit adults) from their dying sister, the viewer'due south middle is fatigued to the vacated bed and useless medicines in the rear.

The frieze won wide approval in Berlin, and Munch was of a sudden collectible. "From the combination of crude Nordic delight in color, the influence of Manet, and a penchant for reverie, something quite special springs," one critic wrote. "It's similar a fairytale," Munch rejoiced in a letter to his aunt. But despite his pleasance in his overdue success, Munch remained far from happy. Some of the strongest paintings in the serial were those he had completed the most recently, chronicling a love affair that induced the misery he often said he required for his art.

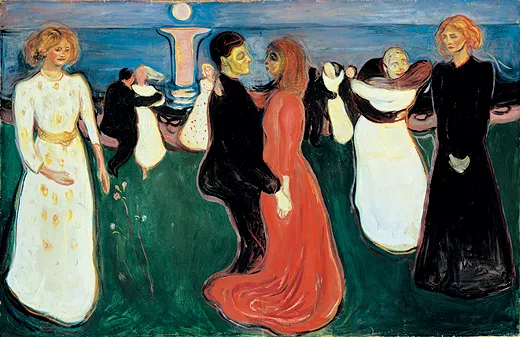

In 1898, on a visit to Kristiania, Munch had met the woman who would become his cruel muse. Tulla Larsen was the wealthy daughter of Kristiania's leading vino merchant, and at 29, she was still unmarried. Munch'southward biographers have relied on his sometimes conflicting and far from disinterested accounts to reconstruct the tormented relationship. He starting time set eyes on Larsen when she arrived at his studio in the company of an artist with whom he shared the infinite. From the outset, she pursued him aggressively. In his telling, their thing began almost against his will. He fled—to Berlin, then on a yearlong dash across Europe. She followed. He would refuse to see her, and then succumb. He memorialized their relationship in The Dance of Life of 1899-1900, set on midsummer'south night in Aasgaardstrand, the seaside village where he once trysted with Millie Thaulow and where, in 1897, he had purchased a tiny cottage. At the center of the motion-picture show, a vacant-eyed male character, representing Munch himself, dances with a woman in a red wearing apparel (probably Millie). Their optics do not meet, and their stiff bodies maintain an unhappy distance. To the left, Larsen can exist seen, golden-haired and smiling benevolently, in a white dress; on the correct, she appears once again, this time frowning in a black wearing apparel, her countenance as dark as the garment she wears, her eyes downcast in bleak thwarting. On a light-green lawn, other couples trip the light fantastic lustfully in what Munch had called that "deranged trip the light fantastic toe of life"—a trip the light fantastic toe he dared not join.

Larsen longed for Munch to marry her. His Aasgaardstrand cottage, which is at present a house museum, contains the antiquarian wedding breast, made for a bride's trousseau, that she gave him. Though he wrote that the affect of her "narrow, clammy lips" felt like the buss of a corpse, he yielded to her imprecations and even went so far as to make a grudging proposal. "In my misery I retrieve y'all would at least be happier if we were married," he wrote to her. Then, when she came to Germany to present him with the necessary papers, he lost them. She insisted that they travel to Dainty, as French republic did not require these documents. Once there, he escaped over the border to Italian republic and somewhen to Berlin in 1902 to phase The Frieze of Life exhibition.

That summertime, Munch returned to his cottage in Aasgaardstrand. He sought peace, but drinking heavily and brawling publicly, he failed to find it. And then subsequently more than a year's absence, Larsen reappeared. He ignored her overtures, until her friends informed him that she was in a suicidal depression and taking large doses of morphine. He reluctantly agreed to see her. There was a quarrel, and somehow—the full story is unknown—he shot himself with a revolver, losing role of a finger on his left manus and also inflicting on himself a less obvious psychological injury. Prone to exaggerated feelings of persecution—in his painting Golgotha of 1900, for instance, he depicted himself nailed to a cantankerous—Munch magnified the fiasco in his mind, until it assumed an epic scale. Describing himself in the third person, he wrote, "Everybody stared at him, at his deformed hand. He noticed that those he shared a table with were disgusted by the sight of his monstrosity." His acrimony intensified when Larsen, a brusk fourth dimension later, married some other artist. "I had sacrificed myself needlessly for a whore," he wrote.

In the adjacent few years, his drinking, which had long been excessive, grew uncontrollable. "The rages were coming more and more frequently now," he wrote in his journal. "The beverage was meant to at-home them, especially in the forenoon but every bit the solar day wore on I became nervy, angry." Anguished as he was, he still managed to produce some of his finest work, including a tableau (executed in several versions) in which he uses himself every bit the model for the slain French revolutionary Marat, and Larsen is cast equally Marat's assassinator, the grim, implacable Charlotte Corday. His 1906 Self-portrait with a Bottle of Wine, in which he paints himself solitary at a eatery table, with only a plate, a wine canteen and a drinking glass, testifies to intense ailment. Two waiters stand behind him in the almost empty restaurant, evoking the setting in which he had read of his begetter'due south death.

In the fall of 1908, Munch collapsed in Copenhagen. Hearing hallucinatory voices and suffering paralysis on his left side, he was persuaded by his one-time roommate from the Saint-Cloud apartment, Emanuel Goldstein, to check himself into a private sanitarium on the outskirts of the city. There he reduced his drinking and regained some mental stability. In May, he departed, vigorous and eager to get dorsum to his easel. Well-nigh one-half of his life remained. Nevertheless most fine art historians would agree that the nifty preponderance of his best piece of work was created before 1909. His tardily years would be less tumultuous, but at a toll of personal isolation. Reflecting this view, MoMA devotes less than a fifth of the show to his post-1909 output. "In his later years," explains curator McShine, "at that place are not as many poignant paintings as there were when he was involved with life."

In 1909, Munch returned to Norway, where he began work on an of import serial of murals for the assembly hall at Oslo Academy. Yet in place, the Aula Decorations, as the murals are known, signaled Munch'due south new determination to await on the bright side, in this case quite literally, with a centerpiece of a dazzling sun. In newly independent Norway, Munch was hailed as the national creative person, much equally the then recently deceased Henrik Ibsen and Edvard Grieg served, respectively, as national writer and composer. Along with his new fame came wealth, but not tranquillity. Maintaining his distance from an alternately doting and scornful public, Munch withdrew to Ekely, an xi-acre manor on the outskirts of Oslo that he purchased in 1916 for a sum equivalent to the cost of 2 or three of his paintings. He sometimes defended his isolation as necessary to produce his work. At other times, he implied it was needed to maintain his sanity. "The second half of my life has been a battle just to proceed myself upright," he wrote in the early 1920s.

At Ekely, Munch took up landscape painting, depicting the countryside and farm life effectually him, at starting time with joyous color, afterward in bleaker tones. He besides returned to favorite images, producing new renditions of some of The Frieze of Life paintings. In his later years, Munch supported his surviving family members financially and communicated with them by postal service, only chose not to visit them. He spent much of his time in solitude, documenting the afflictions and indignities of his advancing years. When he was stricken with a about fatal influenza in the great pandemic of 1918-nineteen, he recorded his gaunt, bearded figure in a series of self-portraits as soon as he could pick up a brush. In 1930, after a blood vessel flare-up in his right eye and impaired his vision, he painted, in such works as Cocky-portrait During the Eye Illness, the clot every bit it appeared to him—a large, irregular purple sphere. Sometimes he gave the sphere a caput and sharp beak, like a demonic bird of prey. Eventually, it flew off; his vision returned to normal.

In Self-portrait Between the Clock and the Bed, which dates from 1940-42, not long before Munch's death, we tin can see what had become of the man who, equally he wrote, hung dorsum from "the trip the light fantastic of life." Looking stiff and physically awkward, he stands wedged between a grandad clock and a bed, equally if apologizing for taking upward and then much space. On a wall backside him, his "children" are arrayed, ane above the other. Like a devoted parent, he sacrificed everything for them.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/edvard-munch-beyond-the-scream-111810150/

0 Response to "Art Representing Taking Everything for the Family So They Could Kive Their Dreams"

Post a Comment